Getting Started with Pomodoro: A How-To Guide for Your First Session

New to the Pomodoro Technique? This step-by-step beginner's guide shows you exactly how to run your first focused session, from choosing your first task to taking your well-earned break.

Jonathan Griffin

Productivity Researcher

Starting the Pomodoro Technique is simpler than you think, but most beginners make it harder than it needs to be. Your first day has one goal: track how much effort your work actually requires. Not productivity perfection. Not superhuman focus. Just honest observation of your real effort, measured in 25-minute blocks called Pomodoros.

Francesco Cirillo, who created the technique in the late 1980s, designed it to be learned through an “evolutionary approach”[1] with incremental objectives. For your first session, ignore estimation, ignore optimization, and ignore everything except the basic rhythm: choose a task, set a timer for 25 minutes, work until it rings, take a 5-minute break, and mark an X to track your effort.

This guide walks you through exactly what to do in your first Pomodoro session, the critical rules you must follow, the common mistakes that derail beginners, and realistic expectations for your first day. Even completing a single uninterrupted Pomodoro on day one is an excellent result because it allows you to observe your process[1]. Let’s begin.

Table of Contents

Your complete guide to running your first Pomodoro session

Your First Goal: Understanding the 5 Objectives

How Cirillo's 'evolutionary approach' guides your first day

What You Need to Get Started

The minimal tools required for your first Pomodoro session

Create Your 'To Do Today' Sheet

Pick your tasks and prioritize them

Step 1: Choose Your Task

How to select the right task for your first session

Step 2: Set Your Timer for 25 Minutes

Understanding the classic Pomodoro interval

Step 3: Work Until the Timer Rings

Managing focus and handling interruptions during your session

Step 4: Take a 5-Minute Break

Why breaks are non-negotiable and how to use them effectively

Step 5: Repeat and Track

Building momentum through multiple Pomodoros

Common First-Timer Mistakes

Pitfalls to avoid in your early sessions

What to Expect from Your First Day

Realistic expectations for beginners

Additional Resources

Supporting sections and references

Your First Goal: Understanding the 5 Objectives

How Cirillo's 'evolutionary approach' guides your first day

Francesco Cirillo didn’t design the Pomodoro Technique as an all-or-nothing system. He describes it as an “evolutionary approach” with incremental objectives that “should be achieved in the order they are given”[1].

This means you don’t need to master everything at once. You learn the technique by focusing on one goal at a time. Here are the five objectives Cirillo lays out[1]:

- Objective I: Find Out How Much Effort an Activity Requires

- Objective II: Cut Down on Interruptions

- Objective III: Estimate the Effort for Activities

- Objective IV: Make the Pomodoro More Effective

- Objective V: Set Up a Timetable

As a beginner, your only goal is Objective I.

This is the most common mistake new users make: they try to do everything at once. On your first day, you are not trying to perfectly eliminate interruptions (Objective II) or estimate your tasks (Objective III). You are simply learning to track your work, one Pomodoro at a time, to discover your baseline of “real effort”[1].

This guide is built around that single, foundational goal. By ignoring the advanced objectives on your first day, you set yourself up for long-term success.

What You Need

The minimal setup for your first Pomodoro session

The beauty of the Pomodoro Technique lies in its simplicity. You need exactly three things, and you probably already have them.

The Essential Tools

A Timer. This is your Pomodoro. It can be a kitchen timer, your phone, a computer app, or a dedicated Pomodoro timer. The only requirement is that it can be set for 25 minutes and will alert you when time is up. Francesco Cirillo used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer (pomodoro means “tomato” in Italian), but any timer works[1].

A Pen and Paper. You need something to write your tasks on and to track your completed Pomodoros. Cirillo recommends starting with simple paper sheets rather than complex digital systems[1]. The low-tech approach reduces friction and helps you focus on learning the technique itself.

A Task to Work On. You need at least one activity from your to-do list. It could be studying for an exam, writing a report, answering emails, or coding a feature. The technique works for any focused work.

What You DON’T Need

You do not need any special software, productivity apps, or elaborate planning systems. In fact, Cirillo explicitly warns that “many time management techniques fail because they subject the people who use them to a higher level of added complexity”[1]. On your first day, simplicity is your friend.

While a basic timer is all you need, if you prefer a digital solution, we’ve created a free Pomodoro timer that follows Cirillo’s original design philosophy. It’s intentionally minimal: set your sessions, press start, and focus. No accounts, no feature bloat, no distractions. It works alongside your existing task list, whether that’s pen and paper or your preferred productivity app.

You also do not need to clear your entire schedule or find a perfectly quiet environment. The technique is designed to work in real-world conditions with real interruptions. You’ll learn to handle those as you practice.

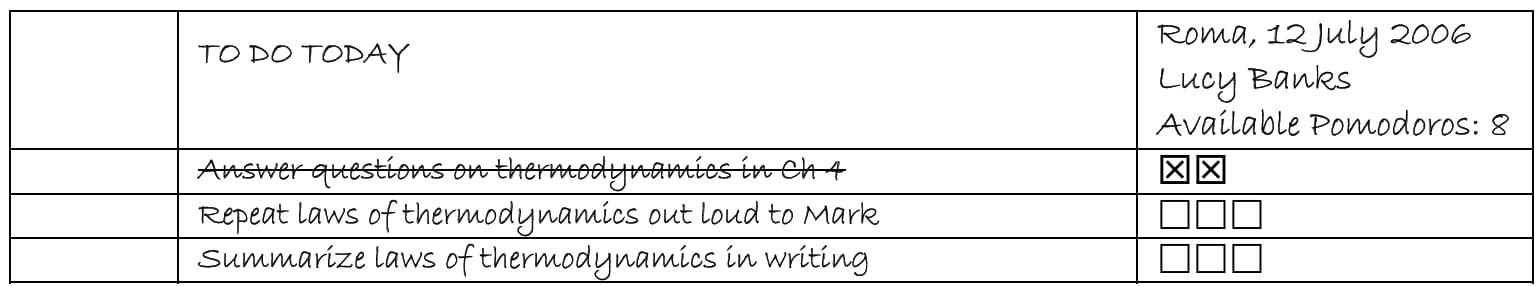

Create Your 'To Do Today' Sheet

Pick your tasks and prioritize them

Prioritize these tasks. Put the most important or urgent ones at the top. On your first day, you might only get through one or two tasks, and that’s completely fine. The goal is observation, not completion.

If you’d like to follow the original method exactly, we’ve created a free To Do Today Sheet template based on Cirillo’s design. Download it as a PDF for printing, or use this editable Google Doc version to customize for your workflow.

Step 1: Choose Your Task

How to select the right task for your first session

Before you set your timer, you need to decide what you’re working on. This is the planning phase, and Cirillo suggests it’s important enough that you might use your very first Pomodoro of the day for it[1].

What Makes a Good First Task?

For your very first Pomodoro session, choose a task that:

- Requires focused mental work. The technique is designed for activities that need concentration, such as reading, writing, coding, or studying.

- You actually need to do. Don’t pick busywork just to practice. Use a real task from your actual to-do list.

- Isn’t too emotionally charged. Save the dreaded, anxiety-inducing tasks for later once you’ve built some confidence with the technique.

Don’t Estimate Yet

Here’s what you should NOT do on your first day: try to estimate how many Pomodoros the task will take. Cirillo is explicit about this. You should only start working on quantitative estimates “after you have begun to master the technique and you’ve reached the first two objectives”[1].

Your first day is about discovering how much effort your work requires, not predicting it. Just write down the task name. You’ll mark Xs next to it as you complete Pomodoros, and at the end of the day, you’ll know the real effort it took.

Step 2: Set Your Timer for 25 Minutes

Understanding the classic Pomodoro interval

Now comes the moment that defines the technique: you set your timer.

The 25-Minute Rule

Set your timer for exactly 25 minutes. Not 20. Not 30. The traditional Pomodoro is 30 minutes total: 25 minutes of work plus a 5-minute break[1].

Why 25 minutes? This duration is long enough to make meaningful progress on a task but short enough that you can maintain intense focus. It’s a timeboxed commitment that feels achievable, which helps overcome procrastination.

The Pomodoro is Indivisible

Before you start, understand this fundamental rule: “A Pomodoro can’t be interrupted; it marks 25 minutes of pure work. A Pomodoro can’t be split up; there is no such thing as half of a Pomodoro or a quarter of a Pomodoro”[1].

The atomic unit of time in this technique is one Pomodoro. You either complete it or you don’t. There’s no partial credit.

Start Your First Pomodoro

Once you’ve set the timer, start it. The Pomodoro is now ticking. This is your cue to begin working on the first task on your “To Do Today” sheet.

As a beginner, you might feel some anxiety from “the feeling of being controlled by the Pomodoro”[1]. This is normal, especially for people who are very oriented toward achieving results. The key is to remember that “seeming fast isn’t important, reaching the point of actually being fast is”[1].

Focus on the process, not the outcome. The timer is your ally, not your enemy.

Step 3: Work Until the Timer Rings

Managing focus and handling interruptions during your session

The timer is ticking. Now you work.

Pure, Focused Work

For the next 25 minutes, dedicate yourself completely to the task at hand. No multitasking. No checking email. No scrolling social media. Just you and the task.

This is harder than it sounds. Your mind will wander. You’ll think of other things you need to do. You might feel the urge to check your phone. These are what Cirillo calls “internal interruptions,” and they’re completely normal[1].

Don’t Watch the Clock

One of the most common beginner mistakes is spending the Pomodoro staring at the timer, watching the minutes tick down instead of actually working. As one user who struggled with this habit described it, they were “literally watching minutes tick by instead of doing my task”[2].

Set the timer and then forget about it. Trust it to ring. Your job is to focus on the work, not monitor time passing. The timer is there to serve you, not to control you. Treat it like a helpful assistant who will tap you on the shoulder when it’s time to stop, not a boss you need to keep checking on.

When the Urge to Switch Tasks Hits

If you suddenly remember something you need to do or feel compelled to work on something else, here’s what to do:

- Acknowledge the thought. Don’t fight it or feel guilty.

- Write it down on your “To Do Today” sheet if it’s urgent, or on your general task list if it can wait.

- Return to your task immediately.

The key insight is that “internal interruptions are often associated with having little ability to concentrate” and “often disguise our fear of not being able to finish what we’re working on”[1]. By writing down the interrupting thought and scheduling it for later, you invert the dependency. The interruption now depends on you, not the other way around[1].

If Someone Interrupts You

External interruptions (colleagues, phone calls, messages) are trickier. If you’re definitively interrupted and must stop working, that Pomodoro “should be considered void, as if it had never been set”[1]. You don’t mark an X. You simply start a new Pomodoro when you’re ready.

For your first day, don’t worry too much about perfecting interrupt-handling strategies. Just be aware that a true interruption means the Pomodoro is void.

The Ring: Stop Immediately

When the timer rings, stop. Immediately.

This is non-negotiable. “You’re not allowed to keep on working ‘just for a few more minutes’, even if you’re convinced that in those few minutes you could complete the task at hand”[1].

The ring signals that “the current activity is peremptorily (though temporarily) finished”[1]. Put down your pen. Step away from the keyboard. The Pomodoro is over.

Step 4: Take a 5-Minute Break

Why breaks are non-negotiable and how to use them effectively

Mark Your Progress

The Pomodoro has rung. Before you do anything else, mark an X next to the activity you were working on[1]. This tracking is the entire point of your first day.

Now, take your break. This is not optional.

The 3-5 Minute Short Break

After each Pomodoro, take a break of 3 to 5 minutes[1]. This break “gives you the time you need to ‘disconnect’ from your work”[1].

Stand up. Stretch. Get water. Look out the window. Walk around. The goal is physical and mental detachment from the task.

What NOT to Do During Your Break

Here’s the critical mistake beginners make: they fill their breaks with other work.

“During this quick break, it’s not a good idea to engage in activities that call for any significant mental effort”[1]. This means:

- Don’t check work email

- Don’t make phone calls about projects

- Don’t read work-related articles

- Don’t plan your next task in detail

- Don’t talk about work with colleagues

If you engage in complex mental activity during your break, “your mind won’t be able to reorganize and integrate what you’ve learned”[1]. The break is when your brain consolidates information and recharges for the next Pomodoro.

The Longer Break After Four Pomodoros

After completing four Pomodoros, “take a longer break, from 15 to 30 minutes”[1]. This extended break allows for deeper mental recovery.

On your first day, you might not reach four Pomodoros, and that’s perfectly fine. But if you do, honor the longer break. Your brain has earned it.

Step 5: Repeat and Track

Building momentum through multiple Pomodoros

After your break, you start again. Set the timer for another 25 minutes. Work on the same task or move to the next one on your “To Do Today” sheet. When it rings, mark another X. Take another break.

This is the rhythm: work, ring, mark, break. Repeat.

The Power of the X

Every X you mark represents “the real effort”[1]. Not your intention. Not your estimate. The actual, completed work.

“What’s important is to track the number of Pomodoros actually completed: the real effort”[1]. This is the foundation of everything else in the Pomodoro Technique.

At the end of the day, count your Xs. That number is your daily output, measured in Pomodoros. It’s objective. It’s honest. And over time, it becomes incredibly valuable data for understanding how you work.

Recording Your Effort

Cirillo suggests that “at the end of every day, the completed Pomodoros can be transferred in a hard-copy archive. As an alternative, it may be more convenient to use an electronic spreadsheet or a database”[1].

For your first day, a simple tally at the end of your “To Do Today” sheet is enough. Write down:

- The date

- Each task you worked on

- The number of Pomodoros (Xs) you completed for each task

This record allows you to observe patterns. “Recording provides an effective tool for people who apply the Pomodoro Technique in terms of self-observation and decision-making aimed at process improvement”[1].

Building the Habit

The first day is about getting comfortable with the rhythm. The second day is about doing it again. The third day is when it starts to feel natural.

Focus on consistency over perfection. “The Next Pomodoro Will Go Better”[1] is the mindset that will carry you through the learning curve.

Common First-Timer Mistakes

Pitfalls to avoid in your early sessions

Most beginners sabotage themselves by making the technique more complicated than it needs to be. Here are the traps to avoid.

Mistake 1: Working Past the Ring

The timer rings. You’re in the middle of a sentence, a calculation, a thought. Just two more minutes and you’d be at a good stopping point.

Stop anyway.

“You’re not allowed to keep on working ‘just for a few more minutes’, even if you’re convinced that in those few minutes you could complete the task at hand”[1].

Why is this rule so strict? Because the Pomodoro is teaching you a skill: the ability to stop. Most productivity problems stem from not knowing when to pause, when to rest, when to step back. The ring is your teacher. When you ignore it, you’re not just breaking a rule; you’re missing the lesson.

Mistake 2: Trying to Estimate on Day One

New users often want to plan their entire day in Pomodoros. “This task should take 3 Pomodoros. That one should take 5.”

Don’t.

Cirillo explicitly states you should only start working on quantitative estimates “after you have begun to master the technique and you’ve reached the first two objectives”[1].

Your first day (and first week) is about discovery, not prediction. Let the data accumulate. Learn how long things actually take before you try to predict how long they will take.

Mistake 3: Using Breaks for “Light” Work

“I’ll just quickly check my email during the break. It’s only 5 minutes.”

No.

Your break must be a true mental disconnect. “It’s not a good idea to engage in activities that call for any significant mental effort”[1] during short breaks. Even activities that seem light (responding to a message, planning tomorrow’s tasks) keep your mind engaged.

The break is when your brain consolidates what you just learned. Interrupting this process undermines the entire Pomodoro you just completed.

Mistake 4: Treating Interrupted Pomodoros as Partial Successes

You worked for 20 minutes, then got pulled into an urgent meeting. That’s 20 minutes of work, right? Can you mark 0.8 of an X?

No.

“If a Pomodoro is definitively interrupted by someone or something, that Pomodoro should be considered void, as if it had never been set”[1].

This seems harsh, but it’s essential. The Pomodoro is indivisible. You either completed 25 minutes of focused work or you didn’t. This binary simplicity is what makes the technique trackable and improvable.

Mistake 5: Chasing Speed Instead of Observing Process

Many beginners, especially high achievers, fall into what Cirillo calls “Ring Anxiety”[1]. They want to prove they can finish tasks quickly. They feel stressed if a task takes more Pomodoros than expected.

This misses the entire point.

“The first thing to learn with the Pomodoro Technique is that seeming fast isn’t important, reaching the point of actually being fast is”[1].

The goal is not to prove you can finish in two Pomodoros. The goal is to find out it takes four, and then discover how to make it three. Speed comes from observation and optimization, not from pressure and anxiety.

What to Expect from Your First Day

Realistic expectations for beginners

Let’s set realistic expectations for your first day with the Pomodoro Technique.

You Probably Won’t Be Amazingly Productive

Your first day is not about crushing your to-do list. It’s about learning a new skill. You’re training yourself to focus in structured intervals, stop when the timer rings, and track your real effort.

If you complete 2-4 Pomodoros on your first day, that’s success. If you only complete one, that’s still success.

“At first, even getting through a single Pomodoro a day without interruptions is an excellent result, because it allows you to observe your process”[1].

You’ll Probably Get Interrupted

Internal interruptions (your own wandering mind) will hit you constantly. You’ll think of emails you need to send, errands you need to run, conversations you want to have. This is normal.

Some people “perceive internal interruptions as things that can’t be postponed,” making “it difficult to complete even a single Pomodoro in a whole day”[1].

The solution is to “set the Pomodoro for 25 minutes and force yourself, Pomodoro after Pomodoro, to increase (and more importantly never reduce) the time you work non-stop”[1].

Each interrupted Pomodoro is data. It shows you where your focus breaks. Don’t judge it. Just observe it and try again.

The Next Pomodoro Will Go Better

If your first Pomodoro gets interrupted, don’t catastrophize. If your second Pomodoro feels scattered, don’t give up. The mantra is simple: “The Next Pomodoro Will Go Better”[1].

This mindset reframes failure. You’re not failing at the technique. You’re learning what disrupts your focus, and you’re building the muscle to resist those disruptions.

What Success Looks Like on Day One

By the end of your first day, success means you have:

- Completed at least one full Pomodoro (25 minutes of work without interruption)

- Marked at least one X to track your effort

- Taken at least one proper break (3-5 minutes of true mental disconnect)

- Stopped working when the timer rang (even if mid-task)

If you did these four things, you’ve successfully learned the core mechanics. Everything else, estimation, optimization, advanced interrupt handling, comes later.

The Learning Curve

Cirillo designed the Pomodoro Technique with an “evolutionary approach” of incremental objectives[1]. Your first objective is simply to find out how much effort an activity requires[1].

You’re not trying to master the technique on day one. You’re trying to complete a few Pomodoros, track them honestly, and observe what happens.

Give yourself permission to be a beginner. The power of the technique reveals itself over weeks and months, not hours.

References

Sources and citations for this article

- 1.Cirillo, F. (2007). The Pomodoro Technique (Version 1.3). Self-published. (Cited on p. 6, p. 27, pp. 6, 9, 15, 19, p. 8, p. 5, p. 4, p. 20, p. 15, p. 26, p. 9, p. 12, and p. 7)

- 2.Sea-Patience-8628. (2025, January 9). I was completely wrong about pomodoro [Reddit post]. r/ProductivityApps.